On a balmy evening last Wednesday, Mews Coach works hosted the first event in its Conversations with Writers series. With all the usual tables and ceramics equipment out of the way, the studio hosted around 40 people. Although many of the speakers may have a recent or upcoming publication, the series aims to foster an environment free from the logic of promotion, where writers can talk more broadly and openly about parts of their corpus, the themes and tensions which interest them and the whole arc of the writing process.

The first guest in the series was locally sourced, the Laureate of Kilburn herself, Zadie Smith. Zadie shot to attention in the literary world around the turn of the millennia for her debut novel White Teeth (2000), for which she won multiple honours. Since then, Zadie has continued to publish novels, short stories, a play, children’s books, and numerous works of essays and non-fiction.

In discussing her non-fiction, Zadie argued for the importance of speaking in your own, true voice, about what you really feel to be true. If this was said by a lesser writer it would seem like a banal truism, but from someone as aware and sensitive as Zadie, who has been in the public- eye since her mid-twenties, one cannot help but see the importance and necessity of her advice.

Central to this argument for writing in your true voice, was removing yourself from discourse. That is, from the hubbub of opinions, debates, often vitriol, which increasingly surrounds us, and which can dictate what ideas and feelings are correct and which are heretical. To Zadie, removing herself from discourse does not mean a hermetic retreat from the world, but rather it begins with silent listening, taking in others opinions, feeling which way the wind blows, without being swept along with it. After this mute removal, Zadie can ruminate and contemplate on what she truly feels, and then the writing just begins to flow (though after a good healthy bit of procrastination).

“As much as discourse is fun and entertaining and I like to argue about it, I would really like to know what I feel to be the truth.”

Josh Cohen delivering a joyous introduction

Zadie argues that freeing your writing from discourse is about not using the language of discourse, or the words of others. For, despite describing herself as ‘a political idiot’, she states that politics is done in language, a point which she makes clear in her recent piece for the New York Times.

“The language makes the argument, if you use the language of other people, social media etc. you’ve clearly lost the argument. Once you say ‘Cultural Appropriation’ its game over.”

But of course, as a writer, things are never so clear cut, and Zadie was keenly aware of the challenges and problems which can befall anyone attempting to undertake such an exercise. For although she argued for the importance of writing sincerely and about your own beliefs, you can’t make yourself the centre of your writing.

“The argument cannot be, “I’m a really good person, so this essay is amazing”, (said in a mocking American accent). You’ve got to take the rhetorical self out of it.”

Smith said that she is trying to get away from, and unpick the idea that non-fiction and the essay are fundamentally about you, what it says about you and your person. For it hinders non-fiction to think its just an expression of your identity. In keeping with one of her heroes, James Baldwin, she knows that this standpoint is unfashionable and runs counter to the beliefs and ideas about writing held by many.

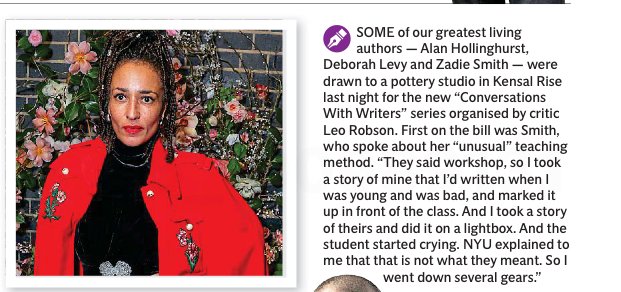

A little feature in the Evening Standard!

These two pieces of advice can seem somewhat contradictory and restrictive. If your writing can’t come from discourse, or from a place of self-expression, then where can it? But what Zadie is aiming for is free, sincere expression, where your words don’t come from others, or aren’t making some performance for your public identity. On that latter point, Zadie gave the amusing but wise advise that it helps to be loved outside of your writing so that you don’t try to be loved from it.

In some ways, Smith’s argument comes back to the origins of the essay itself. Deriving from the French infinitive essayer, “to try” or “to attempt”, the term was first used by Michel De Montaigne (1533-1592) who characterised his works as attempts to put his thoughts to writing. The art of good essay writing is about how you say what you think, not necessarily what you think. As Smith said: “Essays are easy, everyone has opinions”.

The event was an excellent start to the Conversations with Writers series. With all the digressions, contradictions, anecdotes and unfiltered expressions, the flow of the conversation felt refreshingly casual. Deborah Baum skilfully responded to Zadie in a way which allowed the discussion to progress and expand organically, without bluntly changing tack. After questions, the space was swiftly re-organised and drinks and pizzas were served, allowing audience members to mingle and converse (or network, if so inclined). Perhaps on account of the arrival of good weather, it was relaxed, light hearted and enlightening evening. It provided a fitting template for future talks in the series and fulfilled many of the aims we had in creating this series. For news of upcoming events in the series look out for any emails, or check back on this website for updates.

Words by Charlie Jameson